Small Finds #7

Andy Goldsworthy

Come and meet me at the studio, Andy Goldsworthy said; we’ll have a day among the graves.

I drove down from Glasgow on a bright spring morning. I hadn’t been to his place before, but the sight of one of his pieces – a cairn on a hill, like a pine cone of stone – told me I was close. It seemed to say: you are entering Goldsworthy territory.

Not that he would put it that way. He sees himself as an artist working with the land, I think, rather than laying any claim to it. His interventions are patterns of behaviour; how he lives in his environment. He does leave his mark, yes, but only as a dyker builds a wall, or a crow its nest of twigs.

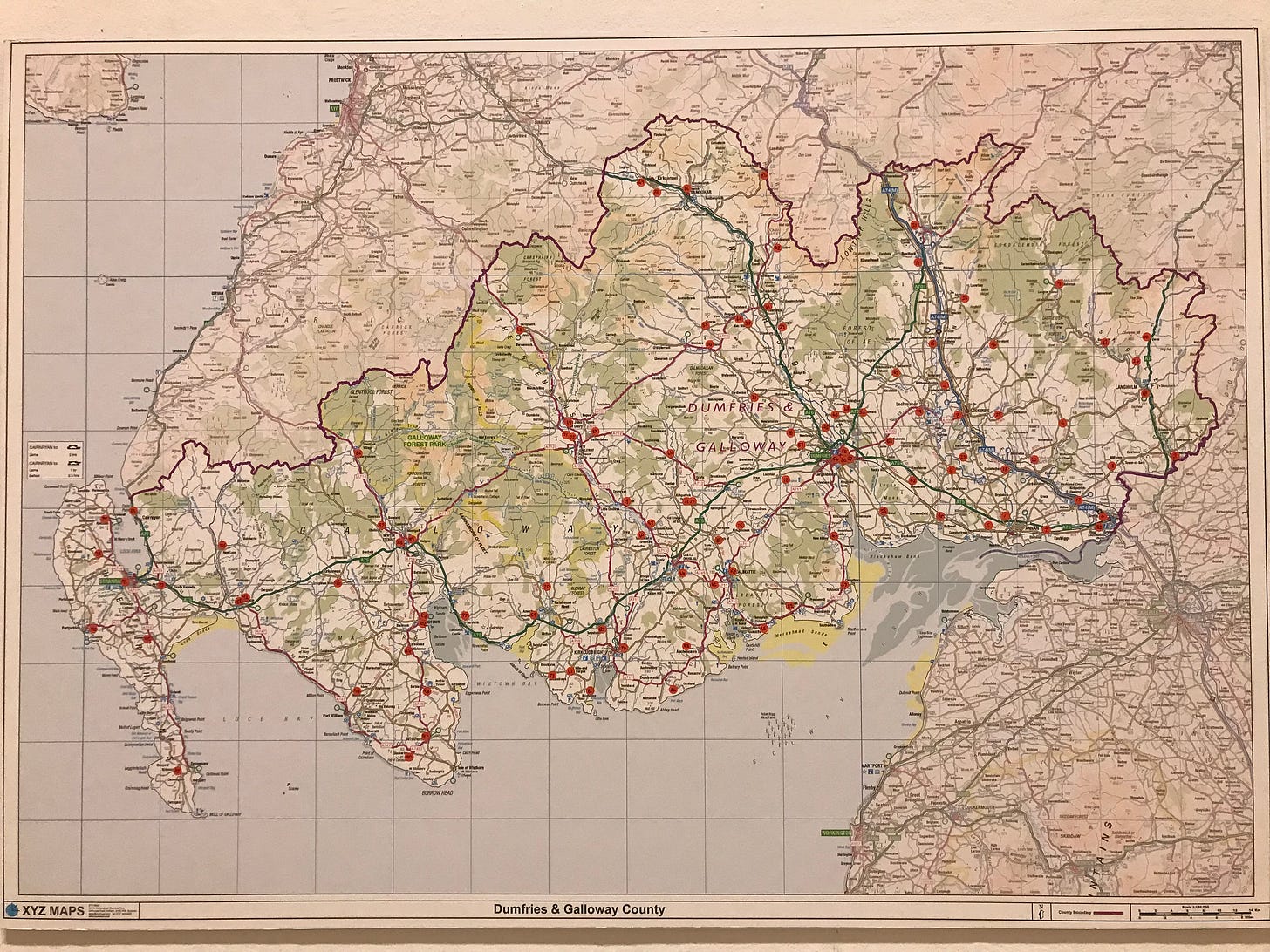

When I got to the studio he made tea and pointed out a map on the wall: south-west Scotland, a rash of red dots showing the cemeteries he’d visited while making his latest work. There were around a hundred, of a total 108. A few more and he’d be done.

We got in his vehicle and went looking for stone.

Goldsworthy is in his late sixties. He has lived in Scotland for many years but his soft voice carries some Yorkshire grit. On his right forearm, I noticed as he drove, was a fading tattoo. I couldn’t make it out, but he explained it was Elvis, a souvenir of his youth in a biker gang, the Asphalt Animals.

We stopped at a kirkless kirkyard enclosed by a red stone wall. Dalgarnock church is long gone, its presence detectable in a low swell. Eighteenth century headstones – carved with skulls and angels – were warm and vivid in the strong early sun.

‘Ah!’ Goldsworthy said. He had found what he was looking for: a mound of stones by the roots of an old tree. He picked out a few, each a good size, and put them in a dusty cloth bag.

He was foraging graveyards in order to make work for his forthcoming show at the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh. He intended to fill a room with this material and call it Gravestones. The idea was seeded three years ago while visiting the grave of his ex-wife Judith, who died in a car accident in 2008. He had noticed a small pile of stone up against the boundary wall. Something about it snagged his mind. What he was looking at, he realised, was stone brought up when graves are dug. In other words, what comes out to make room for the coffin to go in. It was, essentially, a spoil heap created by the gravediggers, a by-product of their labour; most graveyards, it turns out, have one. Goldsworthy feels that these stones are charged with meaning because they have been displaced by the dead. They are symbolic of the people who have died, but are also – in physical reality – part of the place where those people lived.

‘The stones are,’ he has written, ‘a powerful reminder that we are bound to the land – of life and death, of where we come from and where we return.’

Goldsworthy is often described as the UK’s leading land artist, which suggests a grand scale, but much of what he makes is ephemeral: the pattern of hazel sticks thrown in the air; the outline of his body left on frosty grass; clouds of iron flowing orange-red in a stream. Such works bring to mind lines by that other south-of-Scotland artist, Robert Burns: ‘like the snow falls in the river/A moment white—then melts for ever …’

We drove over to where Judith is buried. It’s a lovely spot on a grassy rise looking down over the church to the hills beyond. We stood at her grave.

I told him I was sorry.

‘Yeah. It was tough.’

He pointed to the graveyard wall.

‘The pile of stones was over there. I remember at first I hardly dared pick them up. It was fear of – no, not fear, respect.’

Respect for the material, I think he means. The stones have a purity and clarity. An energy. They are confronting. One of the hardest things about losing someone we love is the physical reality, the thought of their body in the ground. The mind shies from that, if it can; these stones, though, have a weight that drags the imagination earthwards. ‘But Gravestones will be a beautiful work, I think,’ Goldsworthy said. ‘That is really important in everything I do. The beauty makes sense of the pain.’

Judith was the mother of four of his children. He has a teenage son with his present partner. One of the pleasures of making Gravestones has been the company of his boy, helping to gather material. Earlier in the day I had seen many little piles of stone laid out in one of the farm buildings that Goldsworthy uses for his work; the names of the graveyards from which they’d come had been written, by his son, in notes laid on top. The blunt old words were a kind of poem:

Urr, Sorbie, Wigtown, Rigg;

Kirkbean, Kirkinner, Kirkcudbright, Kells;

Applegarth, Beattock, Caerlaverock, Durisdeer;

Lockerbie, Moffat, Wanlockhead, Glebe.

The piece for the Royal Scottish Academy is a step towards a far larger artwork, also called Gravestones, that Goldsworthy intends to make on a hill in the Dalveen Pass, a valley through the Lowther Hills. He has been given the use of the land by the Duke of Buccleuch, and is working with the permission and assistance of Dumfries and Galloway Council, the local authority responsible for the cemeteries. To make the work he will need to find four hundred and fifty tons of material. A dry-stane enclosure, like a sheep fold, twenty-five metres square, will contain it.

‘It will be a sea of stone,’ he told me.

We climbed the steep slope to the site. It took some effort; the walk up is an offering of sorts, Goldsworthy suggested, and will ready the visitor for the presence of the work. For now that can only be imagined. Sticks driven into the ground marked the centre and the corners. We were within a bowl of hills. A river silvered the valley. The moon was an early guest in the afternoon sky.

Goldsworthy described what he thought Gravestones would be like. ‘It is in the most amazingly beautiful place and it will feed the soul. It feeds my soul, walking up here. It has fed my soul walking around the graveyards looking for stone. I’m nourished by that experience. I feel a connection to Dumfries and Galloway that I never thought I would ever have.’

I had, in recent months, been visiting prehistoric tombs. This reminded me of that. Kit’s Coty House in Kent, with its long view over the North Downs. Knowe of Yarso, on the island of Rousay, high above Eynhallow Sound.

The ancestors, in these places, had been raised up. And so it will be here. These stones dug from the ground to make room for the dead were going to be brought close to the heavens and above the countryside from where those people came. ‘It’s a memorial,’ Goldsworthy said, ‘but also an expression of our continued connection to the land. It’s not just the past, it’s the present and the future.’

Gravestones is a work that he could not have made earlier in his life, nor would he have wanted to. He is approaching seventy and, as he pointed out, his father died at seventy-two.

He plans to make the work next year. But even when complete surely there will be room for a few more stones?

‘From my own grave? Yes, I’ll ask that they are put in there.’

And who will do that for him?

‘I think you can figure that one out. The kids.’

Goldsworthy would like to have a grave facing east so that it is possible for a person to stand there before dawn and, as the sun rises, cast a shadow on the headstone. He will, even in death, be involved in making work. His materials and subject, as so often, will be the stuff of darkness and light.

Andy Goldsworthy: Fifty Years is at the Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, until November 2

Farm workers become very much aware of such field stones on fair days from New Year until the silo is dry enough to start ploughing … usually when the Rooks start building their nests. Frost heaving brings big stones to the surface of arable fields and grass parks so they have to be dug up with chains and tractors with fore end loaders, taken by trailer and dumped in a field margin. Old heaps of such field stones and boulders are colonised by shrubs and some by trees reminding us of the work of preceding farm labourers and ploughmen who used to live in the bothies now used for the storage of sprays and dips.

On flights to Baltic States for our holidays we fly over the flat green fields of Denmark - every one of which has tree topped mounds in the middle and on those mounds without tree or shrub cover we can make out the the colour of dry field stone indicating more recent labour.

That's fantastic that you met him. I love his work and ideas. I do my own little Goldsworthy rituals too.